Pluto: Created With Love Through It All (2023 Anime Series)

It takes a deft hand, a warm soul, and a weary heart to portray a world and a tone within that world where one can feel the history dripping out of it’s environments, it’s people, and their collective will that has been tested and tried through their own personal histories and how it relates to that of the state of society and the world the people inhabit as a whole. Even as its artistic trimmings fade into the imitation of life we know it to be, we can’t help but feel that this world we experience through its respective medium continues to turn, even after we disengage with it.

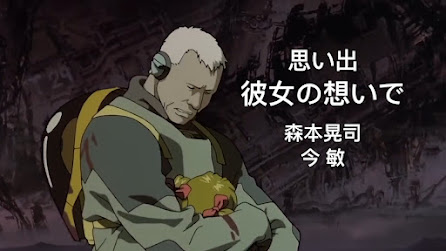

Pluto is an eight episode anime series (specifically an “original net animation” or ONA) based on the 2003-2009 manga of the same name by Naoki Urasawa which is itself a reimagining of “The Greatest Robot On Earth” story arc from manga legend Osamu Tezuka and his trailblazing “Astro Boy” series. While distinctly different from it’s source material, Urasawa’s interpretation of Astro Boy’s fiction is one that is deconstructive while also maintaining respect for the work it is utilizing as a starting point.

The series follows humanoid Europol robot detective Gesicht and his investigation to solve an increasing amount of robot and human deaths around the world. The commonality in all of these deaths, both robot and human, is that all the victims have objects protruding through or positioned near the top of their heads, imitating horns. The case takes an unexpected turn when evidence suggests that it is a robot is responsible for the murders.

All seven of the “greatest robots of the world” which are also the most scientifically advanced, and have the potential to and have been used to fight human warfare seem to be the killer's targets, with the murdered humans being connected to preserving the International Robot Laws, which grant robots equal rights to their human creators. Considering that in the UN charter regarding robot rights, it is said that robots killing humans is contrary to their programming and an impossibility, things are just not adding up. Which drives Gesicht to consult Brau 1589, a robot who was convicted of killing a human eight years ago, in order to get some answers as to how this happened.

Urasawa’s ability to sketch characters and breathe so much authenticity and life into them is, and I mean this with as little hyperbole as I possibly can, like magic. Not just relative to their own experiences but relative to the worlds that they inhabit. The characters of Pluto are no different, in particular its main character Gesicht.

Acutely aware of his robotic existence and how that differs from his human creators, Gesicht, along with every other robot is able to remember with complete perfection their whole lives without missing a beat, thanks in part to the technology powering them and their data storage capability. Puzzlingly there are flickers of a lost memory for Gesicht. One of a particularly violent and furious nature but associated with scraps of hope and sincerity, that he has lost access to. But he is fearful of its content, should it reveal something about himself he finds not only distasteful, but savage and base. In that way he considers himself somewhat fortunate to not remember, but knows there is something behind it. Questioning his own morality and what morality could even mean to a machine like himself.

It is in how many of the robots confront what they have been through at the behest of humanity’s penchant for conflict, that we learn much of the narrative thrust of Pluto. Expected to fight their wars for them, more specifically the recent “39th Central Asian War” and how it affects not just the main characters and highest quality crafted robots, but those that are considered “lesser” by their creators. Coldly thrown into a bloodless atrocity over unconformable hearsay. Each story, each major player peeling back a layer of commonality before thought disparate, unraveling into a web of connections between characters, their interpersonal conflicts, their perceptions of the truth, and the events that take place in their wake. Created against the backdrop of the Iraq War and the US invasion, it draws many allusions to the conflict of the time. The United States Of Thracia (United States of America) invaded Persia (Iraq) after falsely claiming they had robots of mass destruction.

Pluto, in many ways, depicts what one living in the modern world would expect a modern dystopia might look like. And thanks to it’s globetrotting nature, we are able to see how that looks across country lines. Clean, pristine, shimmering and tall stand the most powerful and privileged, as lifeless as they’ve become, having that trickle down to the most vulnerable members of a population. Un-fancied, unloved, and discarded, as nothing more than scrap to be given up when they take up too much space, time, and the only thing that matters to the miserable at the top: money.

As much as Pluto gets right, and it gets so much right so often, its conclusion admittedly left me wanting a bit more in the form of an actual resolution. Even as it’s climax, falling action, would suggest building up to satisfaction in all of the moral complexity, confronting, bittersweet inertia it had been suggesting, it never quite gets there. It goes too fast and trips its way over the finish line rather than having both arms outstretched in confident victory. Its ambiguity is not earned in a way that feels intentionally vague and unanswered, rather slapdash and unfocused. Trying to follow through on a certain point than utilizing its narrative strengths that it had been establishing throughout its run time in a naturalistic conclusion.

With Naoki Urasawa’s works there are always themes to be explore, messages to be imparted through those themes. Not only can we not solve violence with more violence, why should those of an artificial nature, created by us and in our image, not expect to be loved in return for what they provide for us or intrinsically as a being with needs? Are we ready to bear that burden? Not only thoughtlessly sending them to war and leaving the remains to rust and ruin, but treating them as tools to be discarded the moment their usefulness has ended doesn’t suggest a life and a soul to be loved for what they are, not what they materialistically provide to us as their creators, but the cold clockwork of heartless industry. And to a certain extent, we already do that to each other.

Comments

Post a Comment