Devotion: A Familiar Fear

The fear of the unknown is a common theme of the human experience. How do we cope with what we do not understand? Possibly even cannot understand. No matter how hard we try, it is beyond our comprehension. Usually it is a case of understanding to a point where we can realistically protect ourselves and survive the onslaught of that unfamiliarity. But what about the fear of the familiar? Where our day to day lives, familiar settings, and memories become so distorted that they themselves warp into malevolent and dangerous places we wish to escape from. And if we escape from the formerly comfortable confines, the only thing left is to embrace the aforementioned unknowing. I find this to be one of the most effective forms of the horror genre. Reminding us of the fear that can be found right at and beyond our own doorsteps.

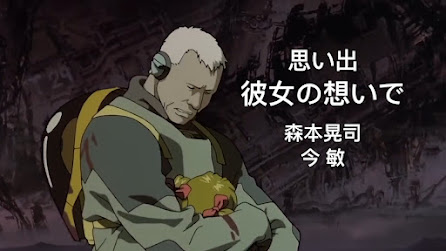

Red Candle Games, the modestly sized independent Taiwanese game development studio (seriously, as of writing this piece they currently have 12 total employees) responsible for one of, if not, my favorite horror games of all time, Devotion. The 2017 masterpiece exploring themes of coming to terms with the atrocities one helped facilitate against the backdrop of “White Terror” the period of martial law imposed during the 1960s, and their follow up project “Devotion” has a slightly larger scope in mind.

Ditching the side scrolling stylized confines of the 2D point and click style found in its forebear, Devotion features fully rendered 3D environments in a freely movable space. With the majority of the game taking place in an apartment complex, more specifically the apartment of troubled screenwriter Du Feng-yu, his wife Gong Li-fang, a retired singer, and his young daughter Du Mei-shin, an aspiring singer. Represented through various years of the family’s life throughout the 1980s.

Feng-yu’s screenwriting career has stagnated as he finds work harder and harder to come by, bills harder and harder to pay, his relationship with his family growing further strained as Mei-shin begins to show signs of a mysterious illness and Feng-yu’s own rigidity and reluctancy to allow his wife to re-enter her field of singing to help with the upkeep.

It is in the environmental design of Devotion that creates its tension as much as its unbroken single shot first person perspective. The color palette a washed out, faded tan creating a sense of history and truly making the Du’s apartment feel lived in, and that all of the life that was once here became nothing but a cold distant memory that all parties would love to forget. The neighborly vibe of the Du family juxtaposing what we know is going to happen is a remarkably smart and effective analog.

As we’re free to explore the apartment to our hearts content, an eerie familiarity begins to permeate its many foreboding and formerly welcoming atmosphere. Exploring Mei-shin’s room we come to understand and see the effects that this girl’s life has had to undergo. The constant strain and strife of her parents arguments take a toll on her to the point where she has lost any sense of comfort and safety she once had as it begins to fragment her own mental health into sharp pieces of uncertainty and stress.

The unsettling atmosphere begins to suffocate even further. We notice that Feng-yu’s head is cut out of or out of frame on all of the family photos, the bathroom door is conspicuously locked in every iteration of the Du’s apartment throughout the years.

Red Candle’s ability to tell a cohesive story while keeping its mystery close to its chest, never showing its cards too early or too late is a remarkable feat. This was a strength of Detention and Devotion is no different in that regard. Through the numerous drawings, newspaper clippings, files, and environmental storytelling, it is able to give us just enough information while keeping its true intentions away from our prying eyes. And it’s use of haunting imagery as well as it’s brief sections of vulnerability through fail states it’s kind of remarkable just how well they have been able to pull it off.

The fact that it is able to do all of this without much real time dialogue is also a feat that is laudable in the space of gaming. Utilizing its mediums unique ability to be interactive, breathing life and building characters in the world around them as opposed to doing so through dialogue or cutscenes, inappropriate for the story that Devotion is trying to tell. Feng-yu and Li-fang’s respective decorations show not only how much their respective careers mean to them, but how they are coping with their subsequent losses of sense of self, while Mei-shin’s room begins to turn from idealistic young dreamer, to terrified self-preservationism.

As we delve further into the history of the Du family, we see footage on the television of Mei-shin’s singing competition that she took part in, seeking to please her parents through becoming a famous singer, just like her mother. However, her performance of her mother's signature song "Lady of the Pier" (碼頭姑娘) comes one point shy of advancing to the next round. Reflected in Du Feng-yu’s disappointment, the audio of the MCs feverishly chanting for an extra point distorting with each repeat is genuinely chilling, and tells us all we need to know about the strength of his aspirations for his daughter.

We learn that after much medical testing and consultation, it is revealed that Mei-shin’s illness is not of the physical nature, but rather the psychological. Unable to accept this, fervently rejecting the notion of his daughter being “crazy” he seeks the aid of cult leader “Mentor Heuh” regarding the folk deity Cigu Guanyin (慈孤觀音), which is based on the household deity “Zigu” who could supposedly help cure his daughter and her singing career.

Continuing further through the years we begin to see just how distorted and obsessive Du Feng-yu becomes with the idea of the cult. Wholly succumbing to the tunnel vision of this idea in his head that it can save his daughter, all the while destroying not just her mental health, but his own life in the process. And that is reflected as the once familiar surroundings of domesticity turn all the more possessive and ominous. The intimate world building and ultimate crumbling of this place that was once a safe and spacious home for a modestly sized family slowly and surely turn further into the disturbing and dreadful.

While I do read this work as a warning against the dogmatic possession of an idea or ideology, I also believe that in it’s setting and characterization it shows how these ideas we can so fanatically cling to can come to not only destroy our own lives, but the lives of our loved ones and those closest to us. Unchanging pragmatism to an idea without introspection and inspection on what these ideas truly entail and who they ultimately effect is an unforgiving and ultimately fruitless way to live ones life that may lead us to be as empty as we made those around us feel. It’s a bitingly relevant interpretation as we collectively descend even further into scarier and dire echo-chambers of our own making.

Comments

Post a Comment