Ni No Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom Review

We feel it, we hear it, we see it. The beginning of the end, the chaos that ensues. It is a loud and encroaching force of modern life, amplified more so by all of the mechanisms in play to keep us aware of just enough to know what it will look like when it all goes. As we’re reminded constantly of the “plan” and our wavering faith in those mechanisms we become panicked. We take it out on others, we fight over trivialities, it’s all a lovely distraction. If we’re sentient, feeling beings that succumb to these base instincts then what does that make our overlords sworn to protect us, safeguard our autonomy and livelihoods? It is up to them, we try to trust them with whatever it is their “plan” is, if it even is one.

Ni No Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom, Directed and written by Akihiro Hino and developed by the fine folks at Level-5, is a strange game. Passioned and puzzling, snappy and clumsy, beautiful and flawed, all in seemingly equal measure. Its scope feels comparatively massive in contrast to its predecessor, not in a “law of sequels” sort of way where bigger isn’t smarter and the big pieces don’t fit together the same as the they were smaller, but in every aspect it strives to make it’s stakes larger, it’s world more full, and it’s characters less humble. Its execution misses its mark as often as it hits but not in a way that feels out of the reach of its development team. rather a lack of focus on the tightness of the original Ni No Kuni.

We begin upon a presidential motorcade, the president, Roland, presiding over the peace summit of which is country is heading up. Just as they begin to make their way across the bridge into the city, a missile explodes, they were too late, peace has lost out in favor of full blown annihilation. Roland wakes up to find himself much younger, intact, and in the middle of a coup d’etat between anthropomorphic cats and mice, the mice attempting to violently overthrow the heir to the Kingdom, Evan Pettiwhisker Tildrum. Mausinger, the mouse-kin advisor to Evan's late father and leader of the insurgency, and assassin of the previous king, Evan’s father, intends to have Evan killed to assume control of the kingdom. Assisted by Evan's governess Aranella, who sacrifices herself for their safety, Evan and Roland escape safely from Ding Dong Dell, with Evan promising to her that he will establish a new kingdom in which everyone can be happy and free. That story itself is functional overall with moments of brilliance throughout its run time. As Evan and his cabinet of like-minded individuals set off to convince the major kingdoms of the land to sign the “Declaration Of Interdependence” (a clever name that I will never stop loving). Ferdinand, an ancient king who once united the kingdoms of the whole world through the aforementioned "Declaration of Interdependence” to rely on each other rather than constantly clash heads, weakening the whole land and opening them up to the apocalyptic threat that eventually does threaten them all. Each king of each respective kingdom holding a “Kingsbond” or a manifestation of their ability to rule, nefarious (and largely absent) thief and former ruler Doloran stealing each King’s Kingsbond with the intention to retrieve his long lost Kingsbond.

The gorgeous, cel-shaded land which can be traversed in a similar way to the original Ni No Kuni, is home to a much different and snappier battle system. Whereas the original had you carefully monitoring magic points, being strategic with your placement in the combat arena, and managing health and status effects in an active time battle system, Ni No Kuni II goes for a flashier, snappier, and much more wieldy system of fulling real time combat. With much less vulnerability and variability you’re free to dispatch your foes with fast slashes and quick ranged attacks relying on a magic meter for the latter and the ability to block and dodge to your hearts content.

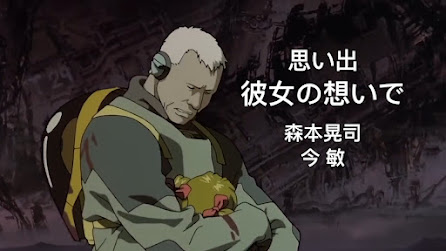

The Studio Ghibli look of the original carries over to the sequel, and its pop and visually arresting appeal is immediately apparent in its environments, character design, beautiful vistas and animations. While there are no Studio Ghibli animated cutscenes as there were in the original the character designs and still images were still done by Yoshiyuki Momose and as such they look remarkable. The man responsible for the music of Studio Ghibli, Joe Hisaishi returning for another fantastic score adds so much emotional texture. Sweeping scores building upon the framework of his previous effort in the original Ni No Kuni, his work fully lives up to the larger size of the sequel. Instrumentation, melody, tone, and emotional-thrust is all top of it’s class from one of Japan’s most celebrated composers.

But we’ve got a Kingdom to build, don’t we? We can’t fight our way to peace! (right?)

That is where building the Kingdom of Evermore comes in. As you complete more mission, gain more support from neighboring states and boost your reputation amongst the world, you have the ability to recruit new tenants to move their livelihoods and skills over to Evermore. This in part does two things: 1. It fills your kingdom with people, and 2. It allows you to utilize their skills to more effectively and efficiently help you gain skills, create new weapons and armor, gain more experience from battles and overtime the more they assist, the better they become at serving the kingdom and it’s king. It is a very robust system that feeds extremely naturalistically and well into the core themes and ideas that the game is trying to convey.

What does not however, is the aforementioned combat system. Its ease of use and accessibility is undermined by its hack and slash style that directly contrasts the nature of the main cast, what they are hoping to accomplish and what their responsibilities are. There are times where a leader much be on the aggressive, no holds barred, not only to get what they want, but to defend with ferocity. However they must also be in equal measure and calculation, well, measured and calculated! Rarely did I ever find a time where I was in a space where I needed to be defensive or consider holding back as opposed to pushing forward and being on the attack. Things like the higgledies, the small fairy like beings that assist you in combat, and the tactics tweaker, were never even necessary for me to engage with. Feels a bit of a letdown when familiars of the original Ni No Kuni were so essential to battle.

And that sense of bravado continues into the large scale battle system which takes place on the overworld, albeit to a lesser extent. What might have benefitted from a Pikmin-style divide and conquer strategy, Evan is flanked by four different styles of units (ranged, melee, magic, etc) on all four sides and must defeat the onslaught of bandits/mercenaries trying to defeat him and his kingdom. And while there is a certain degree of strategy when it comes to rotating each unit to suit strengths and weaknesses of each respective type of unit against another, you cannot send them on their own to flank, to set ranged units on high ground, or to prioritize defending their posts. Most often I found myself pushing forward with no holds barred and using my military strength points (of which there is a finite amount) to replenish my lost soldiers within a given commanders unit.

All of these moving parts bring about it another problem, its uneven narrative and the ambitions it attempts to fulfill. Main characterization, barring Bracken and Leander, additions to the party at about the halfway mark respectively, is weak for the most part. Evan’s idealism is never meaningfully challenged to any large extent, or at the very least does not have as large of a ramification and impact on the narrative as it probably should. He never finds himself having to consider his naivety as it gets in the way of difficult decisions. Whereas someone such as the aforementioned Bracken, has a full character arc, as her idolized leader became the very thing they swore to destroy, to change for the better, to make life easier for everyone else. Grappling with the public blood-thirst and impatience slowly turning him towards vengeance and power-lust. Roland, like Evan, is equally wasted by being given minimal time for actual development and backstory heavily hinted at in the very opening scenes of the game. It is hard to be invested in characterization that has so much underutilized potential and backloaded exposition dumping when the story feels it is convenient.

Speaking of which, that feels an apt way to describe the storyline as a whole. Too much of the main narrative feels under-baked, backloaded, and convenient. Major plot points seemingly drop out of nowhere in the game’s final third. The antagonist never gets enough screen time to become familiar, nor enough development throughout the course of the game to make the revelations given at the ending have any thematic punch. The same can be said for Roland, who throughout most of the game, seems to barely even be aware that he has an empire of dirt waiting for him back in his respective country. Even when he’s finally given a chance to take center stage, the writing does him no favors of developing any further than we already know.

We wait for, and assume the worst. Maybe because we as humans, do so with the intention of being pleased and relieved. When we set the bar so low and end up rising above it, we can feel some degree of safety, confidence, and accomplishment when we are wrong. But what about when we are actually right in our predictions, when the world does “end”, when empires do fall? Will we sit there in the rubble, affirming what we already “believed” would occur, feeling an odd self-destructive sense of comfort? There is value in measured optimism, believing that the brokenness inside our structure and convention is not just survivable, but something that can be used for better, stronger, and healthier days. That for as many people who are comforted by the destruction, there will be those with the desire and willpower to rebuild, even better than before.

While Ni No Kuni II: Revenant Kingdom’s flaws are more apparent and encroach upon its overall experience more than its predecessor. It would unfair to not see its value in its artistic sensibilities and moments of solid execution. It’s beauty breathes loudly, even when it sputters where we wish it had strutted.

Comments

Post a Comment