The Underrated Cinematography Of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain

The element of cinematography is not often given much attention in the medium of gaming. Usually because the extent of “cinematography” in gaming beyond cutscenes is limited to the field of view through which moment to moment gameplay interactions take place in. In most genres there is not much room for meaningful variation, as readability understandably takes precedence over ingenuity.

The cinematic genius of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain often gets lost beneath the myriad of fascination and disappointment that comes with the game’s development taking much longer and costing immensely more than initially planned, the subsequent exit from Konami of director and pioneering video game auteur Hideo Kojima.

That’s not even the half of it either. The game; gargantuan in size, scope, and wealth of interconnected systems is often crushed by its immensely substantial weight. While it’s stealth sandboxing and base building mechanics are among the top of its class, it’s dominant strategy repetition becomes evident the more time you invest into it. Losing its organic and situational reactivity in the process.

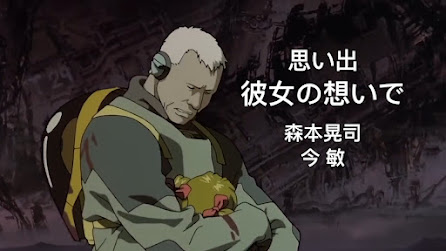

And this is all to say nothing of it’s narrative. A space where Kojima and his team often focused so much of their time and attention to detail into. It is evident to anyone familiar with the franchise that The Phantom Pain eschews authored storytelling for a more open, player driven experience. The man known for his upwards of 30 minute long, non-interactive cutscenes, uses his strengths shockingly sparsely in his final Metal Gear effort. The game featuring much more vignettes, obviously done with a focus on episodic storytelling evidenced by the opening and concluding credits on each story beat. Main missions often involving inconsequential fluff told through mostly static debriefing screens. Story details buried in the expansive amount of audio logs. Unfocused, important aspects often unexplained not in a graceful manner, and (especially considering this game’s development history and documented unreleased Chapter 2 cutscenes) unfinished.

Considering all of this explanation, you may wonder: why would I even bother to bring up something so comparatively inconsequential as cinematic in a video game? I believe this game would have been stronger, more cohesive, if Kojima had instead focused more resources on his strengths as a shot-framer.

Mr. Kojima’s affinity for cinema is well documented. 70% of his body is made of movies by his own admission. And that is evidenced by arguably his most ambitious style of cutscene yet. Rather than pre-established wider shots, The Phantom Pain is more intimate, personal. The proximity between the player and the events unfolding is uncomfortably close but never so much as to obscure us from seeing what is happening on screen.

The movements are deliberate and reactive, rather than predictive. Sudden movements infer a slight delay, heightening the tension as in split-second moments we are unsure of what’s going on before we have to readjust our sight lines and see what it is, not just what Kojima wants us to see, but what we need to see. Shaky camera was the perfect decision for what ultimately ends up to be the most tonally intense and even cohesive Metal Gear game to date. The fact that there is rarely ever a cut, even when transitioning between cutscenes and gameplay makes it feel more connective and seamless.

It is through its cinematic flair and attention that I believe the game’s ultimate themes and messages are made much more smartly than any of the game’s minuscule details within the aforementioned audio logs and mission details. The consequences of obsession and vengeance involve casualties far beyond that of the self. The spread of English being used internationally with such prevalence having a drastic effect on cultural imperialism and unwillingly uniting the world under westernization. And ultimately where I’m going with this: slight misinterpretation leading to reactive decision making. These brief, seemingly abstract visuals capturing in microseconds can stoke such powerful responses from us. Responses of paranoia, misunderstanding, and aggression. It would do us better to fully grasp the concepts of our moments in time, rather than to cling onto emotion over a reasonable facts. The beginning of descent into the post-truth political climate that Kojima himself predicted all the way back in 2001 with Metal Gear Solid 2.

An often criticized piece of Kojima’s style is his perceived over-explanation, his penchant for “long-winded” dialogue, and his non-interactivity with his long cutscenes. But it is within the unsaid of his cutscenes that he is able to say so much more with less than all of the voiced dialogue in the game proper. For the record, I think Hideo Kojima is one of the most important game creators of our time, being one of the very first to synchronize the medium of film, with video games that we are so familiar with to this day. It almost seems that in his possible desire to prove the naysayers wrong, that he’s not merely a “film director making games” he forgot that it was his measured respect of both mediums that helped create some of gaming’s most important works.

Comments

Post a Comment